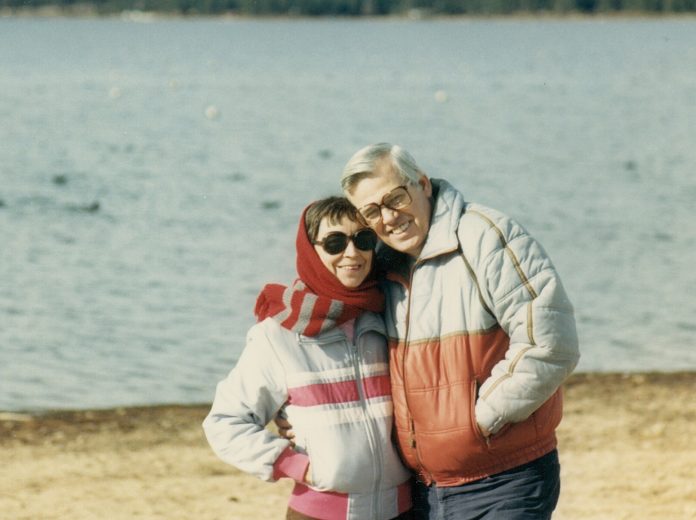

BY BRADY RHOADES: My father gave me more than I could repay – even if I had seven lifetimes.

He taught me how to ride a bike. Play ball. Drive a car. Tie a tie. Do right. Persist.

He imparted little wisdoms: When I was frustrated, or impatient: “The secret to happiness is gratitude.” During tough times, a reminder: “All is well with the universe.” When I yammered on, losing my point and my audience: “Brevity is the soul of clarity.”

The greatest gift he gave me was at the end of his life.

BY BRADY RHOADES: My father gave me more than I could repay – even if I had seven lifetimes.

He taught me how to ride a bike. Play ball. Drive a car. Tie a tie. Do right. Persist.

He imparted little wisdoms: When I was frustrated, or impatient: “The secret to happiness is gratitude.” During tough times, a reminder: “All is well with the universe.” When I yammered on, losing my point and my audience: “Brevity is the soul of clarity.”

The greatest gift he gave me was at the end of his life.

He spent those four months at a hospital, then in hospice care.

He’d been sick for about three years, unable to keep down food, losing weight, weakening, suffering violent falls.

God, he was tired, and not the way you're tired at day's end. His fatigue came after about 28,000 days, the last thousand or so of which were nearly unlivable owing to pain and degradation.

He didn’t fear death, but he had zero interest in anguish, indignity and leaving his loved ones with massive medical bills.

It was clear he’d made his decision. He was 79, 135 pounds, bruised, sick with Stage 4 colon cancer, fashioned in a baby blue dress and getting pushed, pulled and babytalked all over the place, as happens in medical centers.

He stopped eating. He kept yanking the oxygen tube out of his nose. About the third time a nurse tried to re-insert it, he ordered her to leave him the *&$@! alone and went back to sleep.

He told me he liked to go to quiet places within himself. I knew he’d been practicing. He slept a lot, and occasionally chatted with me – gentle talks, sometimes reciting his prides and accomplishments – but he was drifting to those quiet places, hour by hour, week by week.

Our instinct is to fight. My dad had fought all his life. A Depression baby raised in a blue collar family in South Bend, Indiana, he fought for his education and got into Yale University, fought for a decent salary and got out of poverty, fought for civil rights and got to see laws change and friends advance, fought mental illness and got it under control, and he fought for me every step of the way, and got a grateful son at his side.

But his fight was over. He was not going to “rage, rage against the dying of the light.” He seemed committed to a soothing cool darkness.

Through the practice of inner travel, he’d earned whatever serene state he was going to, beyond my comprehension.

In his last waking moment, he gave a great effort and – he was doing it for me, not for himself – sang “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” in tandem, then smiled that crooked smile, somehow got his hand above his shoulder and patted me on the cheek.

He slept for four days then died in tranquility, leaving me at peace, lesson learned, gifted, per usual.